Chapter 21 Abrams Creek

21.1 Basic Information

21.1.1 Characteristics

Location: Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Region: The Smokies and Beyond

Distance: 5.78 mi.

Ascent: 991 ft.

Max. Elevation: 1425 ft.

21.1.2 Highlights

- Accessible, beautiful location in the national park

- Mostly flat walking along a large waterway (practically a river), Abrams Creek

- Many opportunities to splash around in Abrams Creek or the smaller creeks that criss-cross the trail

- A turn-around at one of the best backcountry sites in the entire national park to camp overnight; it is also a great place to rest, snack or picnic, and just hang out before returning to the start.

- The opportunity to level of the challenge level with older kids by taking the trail to Abrams Falls

21.1.3 Ratings

| Hike Name | Beauty | Accessibility | Amenities | Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrams Creek | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

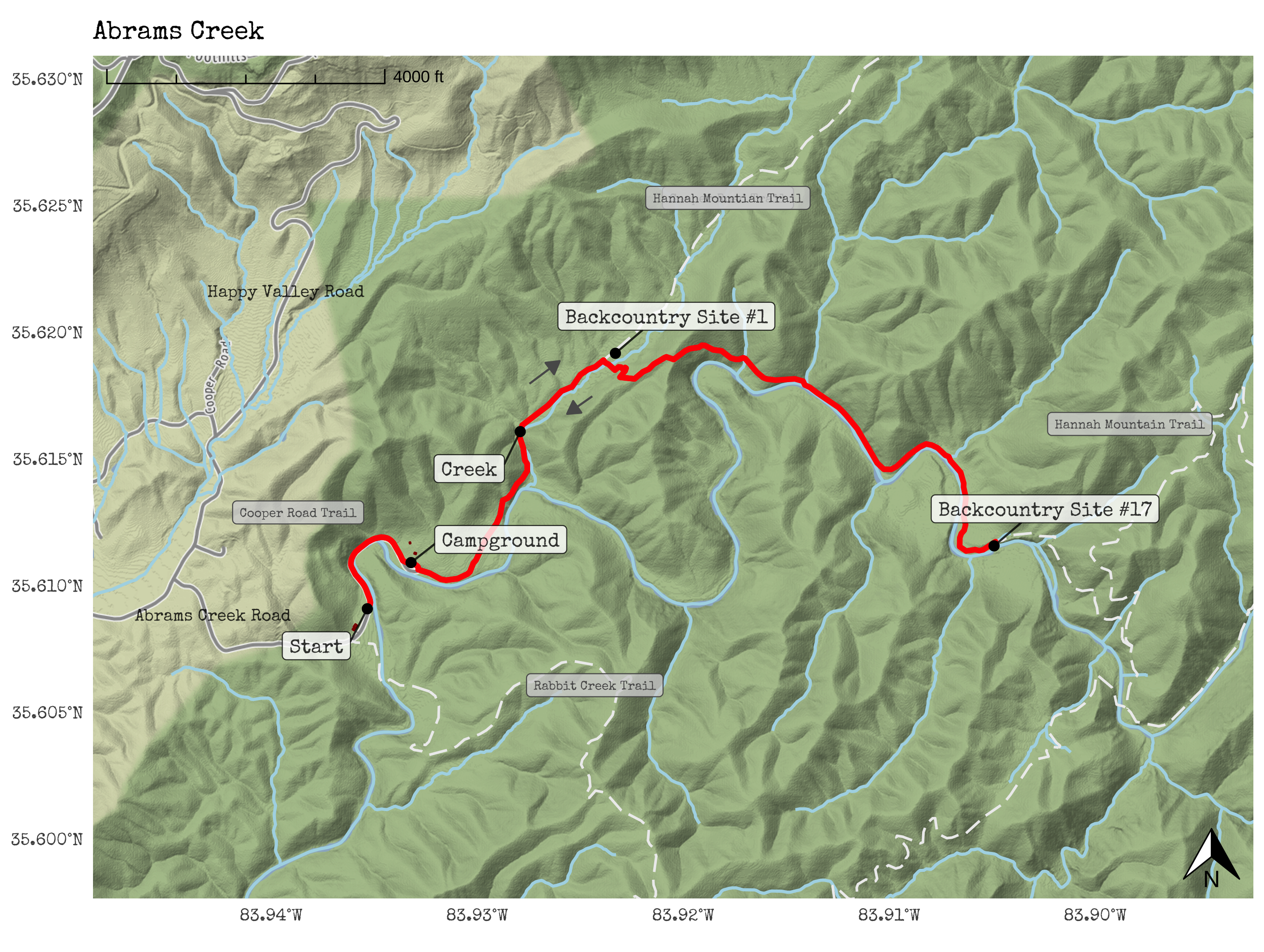

21.1.4 Trail Map

Figure 21.1: Abrams Creek Trail Map

21.2 Trail Overview

Abrams Creek is a great place to start if you live in or around Knoxville. Though accessible, it’s also beautiful. This was the first place we traveled as a family in the Smokies. The single best thing we can say about Abrams Creek is that we always seem to have fun when we go there.

This trail is listed as a quite long—5.78 miles—why it is rated as relatively challenging and better suited to hiking with older children. But, there are many ways to shorten the hike, and we often head to the Creek or Backcountry Site (listed on the map), at 1.0 and 1.3 miles from the start of the hike, respectively. Both include plenty of highlights both are great hikes to do with toddlers (or even younger children being carried). The full hike ends at another backcountry site; it’s one of the finest in the entire national park to camp overnight, and it also makes a great place to rest, snack or picnic, and hang out.

Because Abrams Creek is at a relatively low elevation, it is a great hike in the fall, winter, and early spring, when other parts of the Smokies will be cooler, even requiring a warm coat and gloves for much of the time from December-February It can get warm in the summer, though the access to water to splash and relax in throughout makes it a fine hike for the summer months, too. We recommend bringing waterproof shoes, hiking sandals that are made to get wet, or dry shoes and clothes in your backpack or in the car anytime the weather is warmer.

You might be thinking - as we were - that the ‘Abrams’ in the name Abrams Creek was a reference to Abraham (of the Old Testament). But that’s not the case—at least not directly. Many sources note that Abrams Creek is named for a Cherokee Chief who was colloquially known by the individuals of European ancestry as ‘Old Abram.’ He was a chief for an area around Chilhowee, an important Cherokee village, around the end of the 18th century. See Fink (1934) (cited in Dunn (1976)) for more information.

21.3 Getting There

The drive to Abrams Creek is mostly easy. Getting to Abrams Creek involves driving south from Knoxville past the Tyson-McGee Airport and then Maryville, the largest city immediately to the south of Knoxville. Soon after leaving the outskirts of Maryville, the road climbs up Chilhowee Mountain, atop which is the beautiful Foothills Parkway; the road becomes quite steep, but it is—of course—paved and is still accessible.

After crossing under the Foothills Parkway (an incredible road for a scenic drive!), you drive down into the area outside of the Abrams Creek Trailhead and Campground.

The most reliable way to find the trailhead via Google Maps or other mapping tools is to search for ‘Abrams Creek Campground’ in Tallassee, TN.

It never seems to become crowded at Abrams Creek, but parking can be a bit confusing. This is because the campground is further along the same road the trailhead is on. Also, there are two areas to park for the trailhead. We usually park by the gate to the campground, but you can also park near the large sign with maps of this area of the national park.

21.4 Trail Description

This trail is an out-and-back, starting at the trailhead parking area and heading out as far along the trail as you wish—then returning back to the beginning.

Starting from the parking area, walk along the road beside Abrams Creek. The campground is so small (and almost never full), and it is very rare that you will encounter a car on the walk along the road.

Figure 21.2: The road to Abrams Creek

The littlest adventure involves walking from the trailhead to the Campground (see the marker on the map). This may not sound like much, but it’s actually a great walk along the creek on a wide, gravel road. Moreover, the campground as the campground- like Abrams Creek - is almost never busy, and it’s a great spot to rest by picnic tables and hang out around the creek. The campground is around .40 miles from the parking area, making a trip there and back a little less than a mile.

Do you see the tall pine trees here at the campground? Many of them are Eastern Hemlocks, one of the tallest trees in the Eastern United States. Hemlocks can be identified by their flat needles that exhibit a flat arrangement on the trees’ branches. They can take 250 to 300 years to reach maturity and can live for an astonishing 800 years or more.

You may notice that some of the trees have what appears to be a painted marking on their base. The National Park Service who manage the national park have undertaken an effort to treat Eastern Hemlock trees to prevent them from being infected by the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid, an insect that is considered to be an invasive species–and one that harms many (untreated) Hemlock trees.

Fortunately, the treatment is relatively easy to administer to trees; a chemical very similar to that in anti-tick sprays for pets (like dogs) is dissolved in water, the needles and soil around the base of the trees (which is known as “duff”) is lightly moved, and around a gallon or more of the solution is poured along the base. This treatment is effective at preventing the trees from being infected for five or more years. The park service has treated more than 200,000 trees in this way (National Park Service, n.d.).

Figure 21.3: The campground at Abrams Creek

Walking on from the campground, you will enter a densely wooded area covered by the branches and needles of tall pine trees. You’ll encounter a few hills along the trail, but there’s never sustained climbing that will be needed on this section of the trail.

Figure 21.4: The Cane Creek Trail exiting the campground

After crossing Kingfisher Creek for the first time at 1.0 mile, another crossing of this same creek awaits around 100 yards further from the first crossing. This one is sometimes a little bit easier than the first crossing.

Figure 21.5: Crossing Kingfisher Creek

This is a fun place to rest and snack. To continue on, you’ll need to cross the creek; sometimes, higher water here means we stop here and turn around. At its highest, the water is about six inches deep - nothing dangerous, but it can be difficult to safely and easily walk across the rocks or branches there that ease the crossing.

One way to make creek crossings easier is to grab a large stick to help you to maintain balance as you walk across rocks or logs. Trekking polls (available at outdoors stores) are also great for this purpose, but a stick will do just fine.

After crossing Kingfisher Creek for the first time, another crossing (of this same creek) awaits around 100 yards further from the first crossing. This one is sometimes a little bit easier than the first crossing.

The trail continues to Backcountry Site #1 at 1.3 miles from the trail head. This is a fairly frequently-used backcountry campsite, one used by those backpacking and camping overnight; the national park only allows camping at designated backcountry sites (such as this one) or sites at frontcountry campgrounds–like the one you passed earlier.

The trail continues to Backcountry Site #1 at 1.3 miles from the trail head. This is a fairly frequently-used backcountry campsite, one used by those backpacking and camping overnight. The national park only allows camping at designated backcountry sites, or sites at frontcountry campgrounds–like the one you passed at the beginning of the hike.

This is another great place to stop and rest. If you so choose, you can continue from here. Note the trail sign that is immediately before the backcountry site; it marks the intersection between the Cooper Road Trail, which you have been on, and the Little Bottoms Trail, which branches from the Cooper Road Trail here. To continue further, take the Little Bottoms Trail. You’ll soon cross a small creek and begin to climb—the steepest climb of this entire trail, and a quite steep climb by any metric. At the top of the climb atop this ridge, you’ll find another good spot to stop to rest at 1.5 miles.

Figure 21.6: Spot to rest on top of the ridge

Continue onward along the ridge that you just climbed, soon reaching an overlook at 1.6 miles.

Figure 21.7: A look at Abrams Creek from the overlook along Little Bottoms trail

From here, one of the most prominent peaks in this part of the Smokies—Gregory Bald—is available in the distance. Thereafter, you’ll head down a fairly steep path.

At 2.0 miles, you’ll return to Abrams Creek for the first time since walking alongside it along the road near the campground! This is - again - a great place to stop, rest, and relax—and to splash in Abrams Creek or the small creek, Buckshank Branch, that feeds into it.

Figure 21.8: Meeting Abrams Creek at its intersection with Buckshank Branch

From this point onward, the trail mostly follows Abrams Creek. There are some ups and downs, and the trail can be rocky, but the hiking is mostly free of the ascending and descending you just completed. Around 2.5 miles, you’ll enter an area that was once a farm.

The ‘bottom land’ that was enriched by the run-off from and occasional flooding of Abrams Creek was better for farming (and was—prior to the formation of national park—farmland). This feature gives the Little Bottoms trail its name.

Finally, at 2.9 miles, reach Backcountry Site #17. As we mentioned earlier, this is a great place to rest after a strenuous hike.

Figure 21.9: Backcountry Site #17

From here, turn-around and return to the parking at the start, hopping along creeks larger and smaller, perhaps a little more quickly on the way back than on the way you headed out.

21.5 Nearby

A great trip nearby Abrams Creek is Look Rock and the Look Rock Overlook. It only adds five-ten minutes to the drive and is one of the best overlooks (one that is a little under-rated) in the national park. This is not strictly near the trailhead; instead, it’s nearby the drive back, involving a turn-off just as you pass under the Foothills Parkway (and Chilhowee Mountain) on the return home from Abrams Creek. Search for “Look Rock Tower” or navigate to 7210 Flats Rd., Tallassee, TN 37878 to find the parking for the overlook.

A way to extend the hike, especially with older children, is to continue onward on the Little Bottoms Trail past Backcountry Site #17. Doing so eventually leads further (2.5 miles, one-way) to one of the most-loved waterfalls in the park, Abrams Falls. Note that the total distance of the hike from where you started (at the Abrams Creek Trail head) to this waterfall would be around 11 miles, with some notable ascents and descents along the way. See the Abrams Falls trail entry in this book for another, shorter route to the Abrams Falls waterfall, if interested.

Of course, you can make a reservation to stay at either of the backcountry sites passed along this trail (Backcountry Sites #1 and #17). See the reservation system on the National Park Service’s website for details; reservations must be made prior to the trip and are $4 per person.